Every morning, millions of Americans wake up to news about whether “the economy” is up or down. The Dow gained 200 points – good news! The S&P 500 hit a record high – prosperity! But financial media reports daily stock market movements as if they measure economic health for ordinary Americans. Stock markets actually measure something different: how well publicly traded companies generate profits for shareholders.

While stock markets soar, Americans are struggling to afford groceries, housing, and healthcare. This disconnect reveals a fundamental truth: stock performance measures shareholder returns, not broad economic wellbeing. The stock market tracks how efficiently companies can convert business activities into profits for investors. We’ve been conditioned to celebrate these profits as general economic success.

The Psychology of Small Stakes

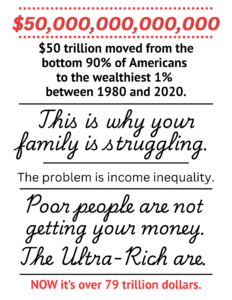

The genius of this system lies in how it makes Americans feel invested in shareholder profits through retirement accounts. Through 401k plans, roughly 60% of Americans own tiny stakes in the stock market. The median 401k balance is around $70,000 – hardly enough to retire on – while the top 1% owns about 40% of all stock. [Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, 2022] That small stake makes people feel invested in a system that primarily benefits large shareholders.

When someone says “my 401k is doing great,” they’re celebrating the same corporate practices that may be making their groceries more expensive and their job less secure. Stock prices rise when companies increase profits through various means: genuine innovation and efficiency, but also through price increases, cost cutting, market consolidation, or shifting production to lower-wage countries. These moves boost profits and share prices while creating mixed effects for everyone else.

The psychological conditioning works because people associate stock gains with their retirement security. The mechanism has fundamentally changed over decades, but the psychological response remains the same.

How the System Changed

In the 1950s and 60s, when General Motors did well, it typically meant hiring more American workers and building more factories. Stock performance correlated with broad economic activity because companies primarily grew by expanding domestic production and employment.

Today, GM’s stock price is more likely to rise when the company cuts jobs, closes factories, or moves production overseas. The metrics that drive stock prices have shifted toward financial optimization rather than productive expansion.

Several key changes accelerated this shift:

Stock Buybacks Became Legal (1982): Companies can now use profits to purchase their own shares, artificially inflating share prices rather than investing in productive capacity, worker training, or research and development.

CEO Compensation Structure Changed: Executive pay exploded from about 20 times the average worker in the 1950s to over 400 times today, with most compensation tied directly to stock performance rather than long-term company health or worker welfare. [Economic Policy Institute CEO Pay Analysis, 2023]

Private Equity Growth: Private equity firms increasingly load profitable companies with debt specifically to extract value for investors, often at the expense of workers, product quality, and long-term viability.

Market Consolidation: Many industries now have fewer competitors, allowing companies to raise prices and reduce services without losing market share.

The stock market increasingly rewards wealth extraction over wealth creation.

The Global Foundation

This domestic system rests on global financial arrangements that most Americans never see. Because oil trades in dollars worldwide, there’s constant global demand for U.S. currency. This allows the United States to create new dollars without facing the inflation consequences that would devastate other countries. [Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, International Dollar Usage, 2024]

That newly created money flows into financial markets, inflating stock prices, real estate values, and other assets. Oil futures contracts often span 20 years, locking countries into dollar-denominated energy commitments extending decades into the future. Even nations wanting to reduce dependence on the United States find themselves bound by existing contracts requiring massive dollar reserves through the 2040s.

This global architecture primarily benefits people who own significant assets – the same shareholders celebrating stock market gains. Regular Americans pay the costs through jobs moving overseas, tax dollars funding military spending to maintain global dominance, and wages that stagnate while asset prices soar.

The Complete Conditioning System

The daily conditioning runs deeper than most people realize. Americans wake up each morning to financial news that trains them to equate corporate profit maximization with their own wellbeing. They work for companies extracting wealth from them, then celebrate when those companies successfully extract wealth, because they own tiny pieces through retirement accounts.

When people sense something wrong – when they cannot afford housing or healthcare despite “good economic news” – they’ve been trained to think the problem stems from personal failure rather than systemic priorities. The psychological trap is complete: even awareness of the problem leads to minimal resistance because people feel dependent on their retirement accounts.

This represents a fundamental conflict between American values and our accepted economic measurement system. Most Americans value health, happiness, liberty, and community wellbeing. Our economic scorecard prioritizes endless profit growth above human welfare. We measure success by how efficiently we convert human needs into wealth for asset owners.

What Real Economic Health Would Look Like

A genuinely healthy economy would show up in measurable ways: housing affordability, healthcare accessibility, wage growth matching productivity increases, economic mobility, and people having time for family and community. Stock market performance might sometimes coincide with these indicators, but stock prices measure different variables entirely.

Consider what we could track instead:

- Housing Affordability Index: Percentage of median income required for median home

- Healthcare Accessibility: Average wait times and out-of-pocket costs for basic care

- Wage-Productivity Alignment: Whether worker compensation grows with productivity gains

- Time Prosperity: Hours per week the median worker must work to afford basic living costs

- Economic Mobility: Percentage of people moving between income quintiles over 10-year periods

A Different Scorecard

The path forward starts with rejecting stock market performance as our primary economic scorecard. Instead of asking “How’s the market doing?” we should ask “Can working families afford to live with dignity?” Instead of celebrating stock gains, we should celebrate when people can afford homes, healthcare, and education without accumulating debt.

The first step involves helping people recognize what they’re actually celebrating when they cheer for stock market records. The system has trained us to measure economic success by how efficiently wealth flows from our communities to people who already own substantial assets.

Every time someone says “the market is up, so the economy is good,” they’re essentially saying “profit extraction is working efficiently today.” We can start measuring what actually matters: whether the economy serves human flourishing or primarily the portfolios of people who already have significant wealth.

The stock market tells us how the rich are doing, not how America is doing. Once you see this distinction, you can start asking better questions about economic health and prosperity.